AI, Transaction Costs, and a Quiet Shift Toward Self‑Employment

Beyond 'will AI take my job?' lies a more interesting question

Something that strikes me in much of the AI‑and‑work debate is how narrowly it is framed. The dominant question tends to be whether AI will replace workers in existing jobs, and if so, in which ones. Even the more nuanced task-based approaches focus primarily on which tasks AI can perform. What gets far less attention is whether AI changes how work is organized in the first place.

From an economic perspective, that omission matters. Technological change doesn’t just substitute capital for labor—it also reshapes the boundary between firms and markets. And on that margin, AI may be exerting a transaction‑cost shock that quietly expands self‑employment and contract‑based work across a much wider set of occupations than we usually associate with the “gig economy.”

This is not a claim that AI is destroying jobs. Rather, it is an analytic observation about how AI may be lowering the costs of operating outside traditional employment relationships—and why that possibility deserves much more empirical attention than it has received so far.

Beyond Substitution: An Organizational Lens on AI

Ronald Coase’s The Nature of the Firm offers the key insight: firms emerge when the costs of using markets such as finding contractors, negotiating terms, ensuring performance exceeds the costs of organizing production internally.

When technology reduces those costs, the logic reverses. Work that once needed to be organized inside firms can instead be purchased on the market.

This mechanism has been central to understanding the rise of freelancing, contracting, and platform‑mediated work over the past decade. In earlier work with my co-author Seth Oranburg, “Transaction Cost Economics, Labor Law, and the Gig Economy” (published in the Journal of Legal Studies), we built on Michael Munger’s book Tomorrow 3.0 to identify four specific transaction costs—triangulation, transfer, trust, and measurement—that explained how digital platforms enabled peer-to-peer transactions that previously didn’t happen. Uber worked because it reduced the costs of consumers finding drivers, transferring payments, and trusting strangers with rides.

AI operates through similar transaction cost logic, but with different mechanisms dominating. To understand its effect on work organization, we need to examine the costs that determine firm boundaries.

1. Production and Measurement Costs (The Alchian-Demsetz Framework, Extended)

The core insight from economists Armen Alchian and Harold Demsetz is this: when output requires interdependent team production and you can’t tell who contributed what, you need a firm with a manager. The firm monitors inputs, hours worked, effort expended, as proxies for output. But when individual contributions are separable and measurable, you can more easily contract for the output directly.

AI affects this margin in two ways: it makes individual contributions more separable when work is collaborative, and it reduces the need for collaborative production in the first place.

First, AI improves measurement and separability in collaborative work. Consider software development. Modular programming already made coding more contract-friendly by creating independent pieces that could be evaluated separately. You could verify whether a specific module worked without needing to understand the entire system. AI development tools push this further, not just in how code is structured but in how it’s specified, tested, and verified. Automated testing can validate each module independently. For example, AI tools can automatically record who proposes a change, what problem it’s intended to solve, and whether it passes standardized tests—creating a clear audit trail that ties individual contributors to specific outputs. This makes individual contributions more transparent and verifiable even in team contexts.

Second, and perhaps more significantly, AI substitutes for complementary roles that previously made team production necessary. This is about reducing the minimum efficient scale of production. Historically, firms existed partly to efficiently bundle complementary capabilities: you need analysis plus editing plus design plus formatting to produce a deliverable report. Individuals working independently couldn’t access all these capabilities easily.

AI changes this by providing many complementary services directly to individual workers. An independent consultant can now produce client-ready reports with AI assistance for data visualization, editing, and formatting, which previously required support staff at a consulting firm. A policy researcher who once needed a think tank’s editorial review, design staff, and institutional publication channels can now use AI tools for editing and professional formatting, while publishing directly through Substack or personal websites reaches audiences without institutional backing.

Large-scale survey research demonstrates this clearly. Traditionally, it required firms with teams of interviewers, coders, and analysts working in coordination. Commercial AI interview platforms like Outset and Listen Labs already enable researchers to conduct hundreds of simultaneous AI-moderated interviews with automated follow-up probing and analysis.

Anthropic’s AI Interviewer—currently an internal research tool—demonstrates that the underlying technology continues to advance in this direction, with systems capable of conducting thousands of in-depth interviews using standardized prompts, automatically transcribing and coding responses, and producing analyzable data at scale.

As these capabilities mature and diffuse into commercially available tools, a solo researcher will be able to execute projects that previously required a research firm’s infrastructure. The independent researcher delivers large-scale results without relying on the firm’s bundle of complementary labor inputs.

For workers, both channels create new possibilities. Better measurement means your work speaks for itself—clients can evaluate what you’ve actually produced rather than relying on someone else’s assessment of your effort. But the substitution effect might be even more important: you can now produce complete, polished deliverables independently when you previously needed a team’s complementary skills. A consultant delivers client-ready analysis with professional formatting and visualization. An analyst produces publication-quality research without needing editorial and design support.

Digital platforms reduced search and payment friction, but AI represents something different: it changes which tasks can be evaluated at all. When AI can directly assess knowledge work quality that previously required managerial judgment, the boundary between what needs firm-based monitoring and what can be contracted shifts fundamentally.

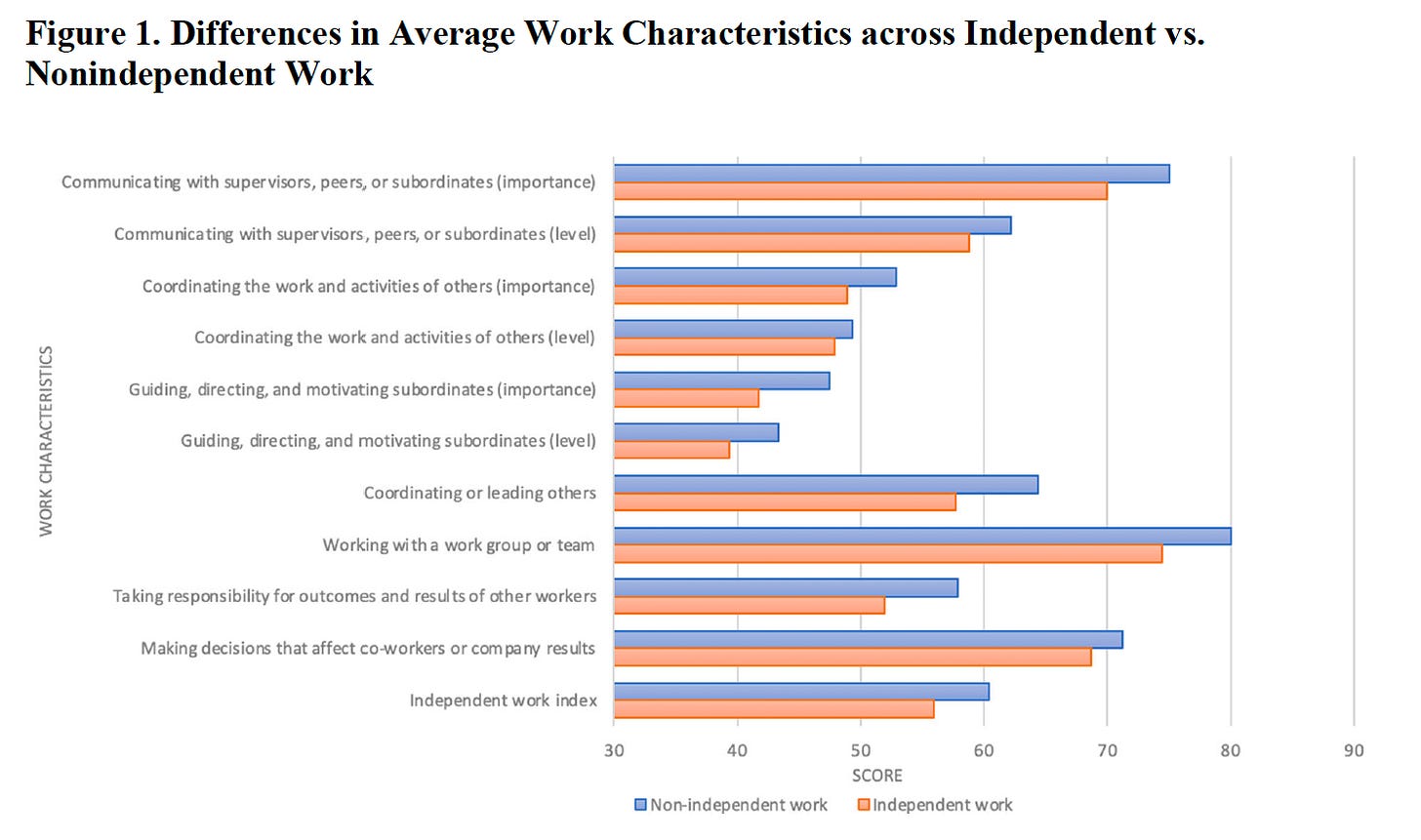

This connects directly to research I did with Paola Suarez, “Employee vs. Independent Worker: A Framework for Understanding Work Differences” (published by the Mercatus Center), examining how work characteristics differ between independent and traditional employment. We found that independent work relies significantly less on:

Team production and coordination

Supervision and responsibility for others’ outcomes

Working in interdependent groups

Figure 1 from our prior research shows these differences clearly—independent work scores lower on precisely the dimensions that favor firm‑based employment.

AI expands the frontier of viable independent work through both better measurement and reduced need for teams.

2. Asset Specificity and Relationship-Specific Investment (The Williamson Framework)

The second mechanism comes from economist Oliver Williamson’s work on asset specificity. When workers invest heavily in learning firm-specific systems, processes, and relationships, they become locked into employment relationships. Those investments are worthless if they leave, creating switching costs that favor long-term employment over independent work.

AI can reduce these relationship-specific investments by standardizing tools and making knowledge more portable. When workers can use the same AI development environments, analytical tools, and knowledge systems across different clients, their skills travel with them.

This standardization effect depends critically on whether AI tools themselves become standardized across firms or remain proprietary. If firms develop sophisticated internal AI systems that require significant learning investments, this could recreate the lock-in dynamics—a possibility I’ll return to in the countervailing forces.

A worker proficient in ChatGPT, Claude, GitHub Copilot, or standard AI-assisted workflows can move between projects more easily. The training and expertise they build aren’t tied to one employer’s proprietary systems.

This portability works in both directions. It’s easier for firms to bring in contractors who can hit the ground running with standardized tools. And it’s easier for workers to maintain independent practices because their capabilities aren’t locked into any single firm’s ecosystem. When skills are more general-purpose, workers face lower risks in operating independently.

3. Search and Specification Costs (The Basic Coasean Framework)

The third mechanism is more incremental because digital platforms already did much of this work. But AI provides some additional improvements in helping both sides find each other and define what needs to be done.

AI-powered platforms can better match workers to appropriate projects and help both sides define deliverables more precisely. For workers, AI tools can analyze market rates to help price services competitively and can translate vague client requirements into clear project specifications before commitment. This reduces information asymmetry—workers know what’s expected and what similar work commands in the market. Less ambiguity means fewer disputes and more confidence in taking on independent work.

But honestly, LinkedIn, Upwork, and similar platforms already reduced these costs substantially. AI’s contribution here is real but incremental. This mechanism matters less than measurement costs and asset specificity.

A Second Thought: Countervailing Forces

Before going further, we should consider what might work against this thesis.

Returns to scale in AI deployment. Large firms may have advantages in building and deploying sophisticated AI systems. Firms with proprietary datasets or specialized AI might make employees more productive than those same workers operating independently. When workers invest in learning firm-specific AI tools, this creates the relationship-specific investments that favor employment—the opposite of standardization.

Input monitoring could favor employment. Here’s an interesting wrinkle from the measurement cost literature: if AI makes it easier to monitor inputs (like real-time tracking of what workers are doing, keystroke monitoring, or attention tracking), this might actually push firms toward employment rather than contracting. When you can cheaply monitor whether employees are working effectively, the traditional disadvantage of not being able to measure output directly becomes less costly. This could reinforce employment relationships in some contexts even as output measurement improves in others.

Coordination complexity in AI-augmented work. Some AI applications might increase rather than decrease the value of tight coordination and co-location. If AI creates new forms of complex interdependencies, this could favor team-based employment over contracting.

These countervailing forces are real. The net effect of AI on firm boundaries will depend on which mechanism dominates in different occupations and industries. But they don’t negate the core mechanisms—they constrain how broadly and deeply the shift toward independent work can go.

The Empirical Questions We Should Be Asking

The theoretical logic is clear: AI reduces several transaction costs that historically favored firm-based employment. What we don’t know yet is whether this is actually reshaping how work gets organized and if so, how broadly and in which directions.

The mechanisms outlined here push toward expanded independent work, but they won’t operate uniformly. Firms with sophisticated AI infrastructure may create stronger productivity gains for employees than those same workers could achieve independently. The shift isn’t universal or inevitable—it’s conditional on occupation, industry, and the specific AI applications involved.

There are concrete empirical questions we could examine. Are AI-intensive occupations seeing faster growth in self-employment? Are workers in fields with high AI adoption more likely to transition from employment to contracting? Do occupations that already exhibit low coordination requirements and high output separability—the “independent work profile”—adopt AI faster?

These questions are empirically tractable, though data limitations exist. Yet I haven’t seen them seriously examined in the AI-and-work literature. Getting answers matters because the implications extend well beyond understanding labor markets—they shape how we design the institutions that will govern work in an AI-augmented economy.

Why This Matters (Even Without All the Answers Yet)

Much of our social insurance system assumes people work as W-2 employees for single employers. If AI makes independent work more productive and feasible—not by pushing people out of jobs but by making contract-based arrangements genuinely more efficient—then we face growing institutional mismatches.

When someone works on projects for multiple clients simultaneously, employment-based health insurance stops making sense. Labor law built around measurable work hours becomes difficult to apply. Labor policy scholars Seth Harris and Alan Krueger have argued this challenge is fundamental for independent workers: minimum wage protections may simply not fit when work hours cannot be reliably measured or attributed to specific intermediaries.

AI seems to intensify this challenge: when a developer uses AI to compress three days of work into six hours while juggling multiple clients, what would applying hourly wage floors even mean? The question becomes not just administratively difficult but conceptually puzzling—you’d need to determine whose ‘hours’ are being worked when the traditional relationship between time, effort, and output has fundamentally shifted.

The portable benefits conversation has moved from think tank papers to actual state pilots and federal proposals. That momentum reflects a growing recognition: safety nets built around W-2 employment don’t work well when work happens across multiple clients and projects. If this AI-driven reorganization accelerates, the mismatch between how we organize social insurance and how work actually gets done will only widen.

A Different Kind of Reorganization

AI may be changing the boundary between firms and markets—and we’re not paying nearly enough attention to this margin. The dominant frame in AI-and-work discussions is substitution: will AI replace workers or augment them?

But Coase taught us that the firm-market boundary is endogenous to transaction costs. When those costs shift, work organization shifts too. Whether this produces a major labor market reorganization remains uncertain—evidence is developing and effects vary by occupation. But the theoretical mechanisms warrant empirical attention now, not after the fact.

The conversation needs to expand beyond “will AI take my job?” to “how will AI reorganize how we work?” That question will shape not just labor markets but social insurance, labor regulation, and economic measurement for the economy we’re building.

Final Note: If you’d like to read the full JLS paper but can’t access it through the paywall, just drop a comment or send me a message—happy to share the published version.

Fantastic framing of AI through the transacton cost lens. The point about AI reducing minimum efficient scale really clicks - I've seen consultants deliver stuff that used to need whole teams, just with AI handling the complementary tasks. What's interesting is how this creates a sorting mechansim where the best independent workers might actually outproduce firms now.